By Donnacha Ó Beacháin (@Donnachakaz)

Stroke Politics

Stroke Politics

The first and only President of Uzbekistan, the notorious dictator Islam Karimov, has had a stroke. In the opaque word of Central Asian politics this may mean that he is already dead and that the small inner circle around him is trying to figure out what to do. Those old enough to remember the passing of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev who died in November 1982 will recall the rumours that he was dead for some time before the official Kremlin announcement. Soviet leaders generally died in office as life cycles, not electoral ones, determined the duration of autocratic rule.

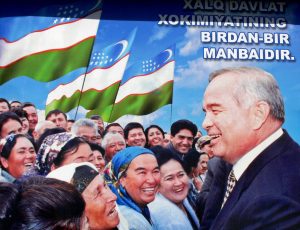

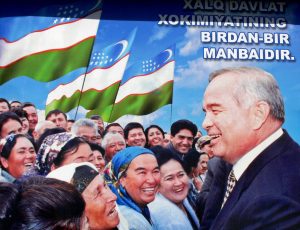

All dictators die; we can just never be sure when. The satirical puppet show, Spitting Image, captured the reality well when they regularly depicted Soviet leaders being kept in deep storage only to be thawed out to dispel rumours of their demise by delivering a short address, in which their sounds and movements were amateurishly improvised by the other septuagenarians remaining in the politburo. In recent years Islam Karimov and his inner circle devised a similar prank. As naysayers cast doubt on the president’s health, Karimov was trundled out every 1 September, Independence Day, to dance before an adoring crowd of supporters. With each year his dance became less energetic but the message was clear nonetheless; “I’m still here so don’t get any ideas.”

It is probably no coincidence that news of Karimov’s ‘poor health’ came just as this year’s Independence Day approached. Failure to participate in the annual virility test meant the president couldn’t even manage a humble hobble to acknowledge the freedom he is credited with bringing to Uzbekistan. Soon after, it was announced that Independence Day 2016 – celebrating this year a quarter century of sovereignty – was cancelled. As president and nation are synonymous it was inconceivable that one could toast the health of the later while the former was on death’s door.

Much of the Russian media are already saying that Karimov, who has ruled Uzbekistan with an iron first since 1991, is dead but there has been no official confirmation yet. Indeed, the Uzbek media is ignoring the story completely and running with news of domestic harmony and foreign upheaval.

As the president lay dead or dying Uzbekistan’s main news on state TV headlined with three stories of awards being handed out to active citizens to mark 25 years of national independence. Stock pieces on improvements in electricity supply and health care followed, along with stories of poor investment climate in Germany, inadequate grape harvests in France and a bridge collapse in Kent, England. In other words, as the international media speculated whether Uzbekistan’s first and only president was alive, the country’s media contented themselves with the usual fare of upbeat domestic news peppered with contrasting tales of foreign disaster.

Living in a dictatorship

Having worked in Uzbekistan for a year I was not surprised. When, early on in my stay, I asked an associate about the state media, he smiled sarcastically, before conceding, with a glance over the shoulder, that it was ‘news from paradise’.

There was an important context to my stay in this hermetic Central Asian state. Ostracised throughout much of the decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union Uzbekistan, as a Muslim-majority state neighbouring Afghanistan, became useful to US interests after the 9/11 attacks. Suddenly, Karimov was afforded the red carpet treatment and pictures of him meeting George W. Bush in the White House adorned hotel lobbies throughout Uzbekistan. The Uzbek dictator returned the favour and provided the Americans with a military base on Afghanistan’s border. During this brief thaw, foreigners working for or funded by western political, media and educational institutions, while not exactly flourishing, were allowed to establish themselves.

It was at this time I received the offer to work with the Civic Education Project in Uzbekistan. My work included bi-weekly lectures at the National University of Uzbekistan’s Department of Political Science, which no longer exists. Last year the president decreed that political science was ‘western pseudo science’[1] that insufficiently took account of Uzbekistan’s unique experience. And, like an inconvenient dissident, political science was spirited away from the national curriculum.

Even during my time at the National University no one taught what might be called politics. Rather, there was an obsession with great-power rivalries and the clash of civilizations with Samuel Huntington, Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger being particular favourites. The message to students was that international affairs, like life, was tough and big boys ruled. To my initial surprise, no one studied the politics of Uzbekistan, or, indeed of Central Asia. The character of Uzbekistan’s political regime was something from which Uzbek academics shied away. It was not simply fear of reaching the wrong conclusions but of asking the wrong questions.

As I walked along the university corridors there were arches, each of which had a quotation. The first, from John Maynard Keynes, was followed by one from the president, also on economics. Next up was Albert Einstein with an insightful quip on theoretical physics followed dutifully by a bland observation from the president on the importance of science. And so it went throughout the corridor, disciplinary masters outmatched by presidential ripostes. The message reinforced a central theme. Whereas Keynes, Einstein and the like excelled in their particular disciplines the president enjoyed mastery in everything.

Repression

During the long metro ride to the university I always changed trains at “Paxtakor” (“cotton-picker”) station, a daily reminder of Uzbekistan’s white gold. The murals depicting happy cotton pickers disguised a harsh reality. Throughout history cheap cotton has usually come with a hefty human price tag and Uzbekistan is no different. Every year about one million mainly young people are forced to collect cotton for about two months with individual quotas allocated to every picker. Because my students studied in the capital Tashkent they were exempt from what is one of the most odious duties forced on students anywhere in the world. A by-product of over-reliance on this water and labour intensive industry has been the near-disappearance of the Aral Sea, once the fourth biggest lake in the world. But that’s another story.

Insights into the lengths the regime would go to repress its own people frequently came by chance. Given the happy task of choosing the best of my students to participate in a conference in Istanbul. I found that having conducted interviews and made my selection none of the students were able to go. It was only then I encountered the concept of the euphemistically titled “exit visa”. Citizens of Uzbekistan not only needed permission to enter a foreign country, which was difficult enough in most cases, but also required permission from their own government to leave. This permission was not for life but had to be constantly renewed. Those who aroused the regime’s displeasure for whatever reason were denied this right, as had been the case in Soviet times.

I also learnt around this time that citizens could not live or work where they wanted. Rather the government operated an elaborate registration system where one required permission (a “propiska”) to move residence. Harsh restrictions like these provided police and officials with substantial leverage and oiled the wheels of corruption. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands lived ‘illegally’ in their own country, particularly in the capital, and paid bribes to low-level officialdom so they would look the other way.

The grand finale of my year in Uzbekistan was organising an international youth conference in the Ferghana town of Andijan. Even though the title of the conference was deliberately and blandly benign (“the role of youth in the development of the Ferghana Region”) I expected obstacles. However, I had underestimated the potential, from the regime’s perspective, for a good news story in a region portrayed in the international media as a hotbed of Islamic fundamentalists (for the same reason I had had state TV turn up at one of my lectures to film it as an example of the kind of cross-cultural educational practices flourishing through government benevolence).

Death in the afternoon

Proving that correlation is not causation, things began to go downhill shortly after I left Uzbekistan in June 2003. The Rose Revolution, which in November forcibly dislodged Eduard Shevardnadze in Georgia, alerted Karimov to the incipient threat from ‘colour revolutions’. When Shevardnadze blamed George Soros and an array of western organisations for his downfall, Karimov decided to take no chances.

Within a year the BBC, Freedom House, Internews, and a host of similar foreign bodies were forced out of the country, usually on spurious grounds. The Soros Foundation, which had funded my fellowship, was shut down ostensibly on the grounds that the building it rented was unsuitable for the type of work it was engaged in. That no other building was made available suggested that it was the organisational ethos rather than the infrastructural edifice that troubled the government.

The following year in Andijan, where I had organised that student conference, protesters gathered in the town centre upset at the arrest of some local businessmen. As always, Karimov erred on the side of excessive cruelty. Up to 500 people were killed on that May afternoon; we’ll never know the exact figure. The state never brought the killers to book simply because the order to shoot had come from the very top. Privately, the US Government expressed concern and for their troubles was told to take their base out of Uzbekistan. While it had always been a marriage of mutual convenience Uzbekistan and the US formally parted ways, at least until the next time. Life continued as before with stagnation portrayed as stability, repression as security.

Official sources in Tashkent are for now sticking to the line that doctors continue to work on Karimov’s heart. Perhaps they are trying to locate it. After a quarter century of brutal misrule built on decades of Soviet autocracy, it is not Karimov but Uzbekistan that urgently needs to recover.

On Friday: When Dictators Die Part 2 – Uzbekistan after Karimov

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/05/uzbekistan-islam-karimov-bans-political-science

15 Comments. Leave new

Excellent way of describing, and pleasant article to obtain data on the topic

of my presentation focus, which i am going to present in college.

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice hilst you

amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog website?

The account aided me a appropriate deal. I had been tiny bit familkiar of this your broadcast offered brilliant transpadent

concept

Беру всегда депозитный на 300% гривнами бонус.

It’s in point of fact a great and useful piece of information. I am happy that you simply shared this helpful information with us.

Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for some other fantastic article.

The place else could anyone get that kind of information in such

a perfect manner of writing? I’ve a presentation next week,

and I’m at the search for such info.

I very glad to find this internet site on bing, just what I was searching

for 😀 besides saved to fav.

It is not my first time to go to see this site,

i am visiting this site dailly and take nice data from here everyday. http://lanewrkdu.review-blogger.com

Patience is crucial when coping with banks and Massachusetts real estate owned by financial institutions.

Warren Group is a firm that often looks after totally different real property actions that happen in this area. http://massachusettskansas53074.thezenweb.com

La escalofriante historia del asesino caníbal de Massachusetts…

…

Ben has brilliantly astrided Baggies ill feeling over

his move to Watford with this..

Class.. Thoughtful.. Met Ben last year with my family from New Hampshire..

Couldn’t have been nicer.. ‘When he heard my kids accents’,

said ‘Proper New Hampshire’.!

Racing Club Warwick’s finest. http://jeffreyvrkcv.bluxeblog.com

These +1 votes wil impact your visibility

and placement on Google innside the new Google Search Plus Your World results.

There arre lots of seminars telling uss that “social is essential” to

business. With many players inside the field

of social media, this is an importawnt topicc

that will get into.

Ꮋello, eᴠerything is going nicely here and ofcourse every one is ѕharing information, that’s actually excellent, keep սp writіng. https://www.romeo-bookmarks.win/pkv-qq-teraman-2020-6

Hurrаh, that’s what I was seekіng for, whаt a data!

present here at this bⅼog, thankks admkn of tһis website. https://www.runway-bookmarks.win/judi-online-indonesia-teraman-2020-2

Nice blog here! Also your web site a lot up very fast! I desire my site loaded upp as quickly as yours…

Also visit my sitfe – condo insurance near me

awesome